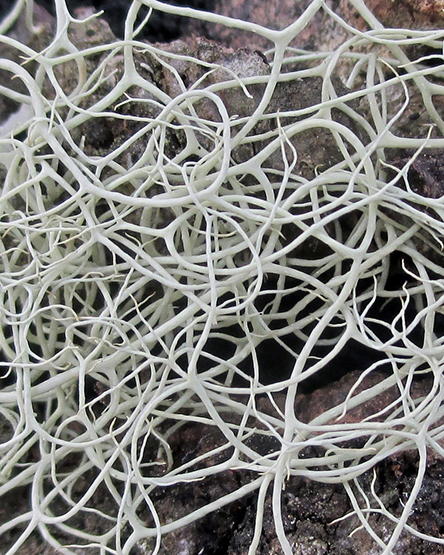

Dried lichens in the Duke Gardens teaching collection, by Angela Claveria.

Whether brightly colored or dull and drab, it’s impossible to go anywhere in the world without encountering weird and wonderful lichens growing on living trees, stumps, rocks and other substrates. Often mistaken for plants, lichens are an entirely different class of organism, with deep and unexpected ties to North Carolina’s ecology and the history of Duke Gardens.

Lichens—fungi that live in intimate associations with algae or photosynthetic bacteria—are textbook examples of symbiosis. In fact, the concept of “symbiosis” (literally, “together life”) was first introduced by Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener in 1867 to describe lichens. No other symbiotic relationship had been discovered before. The intimate association of the two partners is mutualistic: the fungus provides a home for their algal or bacterial partner, who in turn supplies carbohydrates—produced via photosynthesis—to the fungus.

Worldwide, there are an estimated 20,000 species of lichen fungi, found in nearly every ecosystem on all continents. Lichens can even comprise the dominant “vegetation” in habitats where plant growth is limited—for example, in places too cold for plants, like tundra; where soil is sparse or absent, like flat rock outcrops; or where water is scarce, like deserts. To thrive, most lichens need to be in places where they aren’t shaded out by plants, which grow taller. Most are also very sensitive to air pollution, so in addition to light, they need clean air.

Lichens often grow alongside mosses because the two share similar ecological requirements. For example, the Kremen Interpretive and Kathleen Smith Moss Gardens host an impressive diversity of lichens as well as mosses. I’ve installed display signs for some of the lichens there on the rocks, bark and wood where they grow. Look for them the next time you visit the William L. Culberson Asiatic Arboretum (pro tip: bring a magnifying glass if you want to fully appreciate these tiny wonders!).

Did you know that Professor Culberson served as Director of Duke Gardens for 20 years and was a renowned lichenologist? Together with his wife, Dr. Chicita Culberson, he established one of the world’s foremost research programs on lichens during his tenure as Duke University’s Hugo L. Blomquist Professor of Botany. Over the course of his 40-year career, he identified and described numerous lichen fungi new to science, including many species native to North Carolina. I was Professor Culberson’s last graduate student, completing my dissertation in 1997, two years after his retirement from the Botany Department.

Long before my time, in 1975, one of his first graduate students, Jonathan Dey, wrote his dissertation on the lichens of high elevations of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Over 1500 species of lichen fungi have been documented in North Carolina (with new ones being recorded all the time), and over 1000 of them occur in the Southern Appalachians, so Jon had his work cut out for him. I can only imagine what the North Carolina mountains looked like in the 1970s when Jon was exploring them: much less populated and more restricted access, with fewer improved roads. It must have been a much more mysterious and impenetrable place than it is today. In his dissertation, Jon documented over 600 species from high elevation areas of the Southern Appalachians, and described two species new to science in the process.

Organisms that occur at high elevations are cold-adapted species, and as such, are useful indicators of global warming: as temperatures increase, their populations shrink over time. If they can’t adapt as fast as the climate warms (and they usually can’t), they are eventually extirpated from their mountain-top homes (although they may still exist at more northern latitudes). Jon Dey’s dissertation, therefore, provides a critical baseline for comparing historical versus current Southern Appalachian lichen diversity.

In 2017—the year I returned to Duke University to work in the Biology Department—a comparison of Dey’s findings with modern-day specimens from Mount Mitchell State Park was published. At 6,684 feet, Mount Mitchell is the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. The publication’s authors were unable to locate 27 lichen species reported by Dey from Mount Mitchell, including seven rare, high-elevation species. The authors blamed a combination of acid rain, balsam woolly adelgid infestations, and climate change for the decline in lichen diversity. Their conclusions, however, were preliminary because (a) most of the authors’ modern-day specimens were collected in just one day and (b) their specimens were almost entirely from only one high-elevation habitat: spruce-fir forests.

I returned to Mount Mitchell multiple times in 2017, and each time, I observed lichen species not represented in either Dey’s or the modern-day inventory. In 2018, I returned with a permit, students, and a purpose: generating a more complete checklist of lichen species from every high-elevation habitat in the park, and a more detailed comparison of Dey’s specimens with modern-day specimens. After five years comprising over 120 person hours, we were able to relocate 13 of the 27 Dey species that the modern (2017) authors could not find, including three of the rare, high-elevation species named in the 2017 publication. Further, we discovered 72 lichen species brand new to the park.

Four months ago, the results of our intensive five-year study of the lichen flora of Mount Mitchell were finally published. Since we collaborated with the authors of the 2017 publication, we included them as coauthors and published in the same journal they published in: Castanea, the official journal of the Southern Appalachian Botanical Society. Togherf, our combined floristic analyses provide a more refined and nuanced view of the changes to the lichen flora atop Mount Mitchell.

For example, the remarkable diversity of cyanobacterial lichens (nearly 20 species; 8% of the park’s total lichen flora) indicates that acid rain and woolly adelgid impacts are much less than previously thought, because cyanobacterial lichens are extremely sensitive to both pollution and disturbance. This, together with the high number of high-elevation, cold-adapted species that have disappeared in the last 50 years, points the finger strongly at climate change. In addition, the loss of several species of Cladonia (reindeer lichens) since Jon Dey’s time appears to be correlated with construction on Mount Gibbes, a peak adjacent to Mount Mitchell that served as the source of many of Dey’s Cladonia collections. Furthermore, during the process of routine identifications using DNA sequence data, we were excited to discover a species of Parmelia (shield lichen) potentially new to science.

Most importantly, our research allowed us to identify five species of rare, high-elevation lichens in critical need of conservation. Most of these five are protected at the international level, but not at the state level in North Carolina. In our publication, we strongly urged the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program to evaluate placement of these lichens on their statewide rare plant list. We further recommend these five species be listed by the North Carolina Plant Conservation Program.

I am proud of this contribution to the and conservation of North Carolina’s biodiversity, and I like to think both Professor Culberson and Dr. Dey would be very pleased as well. As we all know, the wheels of legislation are slow, but this research was a crucial first step in the protection of these fascinating, imperiled species.

Hypotrachyna densirhizinata

Alectoria fallacina

Lobaria scrobiculata

Parmelia neodiscordans

Nephroma parile