Duke Gardens is forever indebted to the pioneering women who have played an instrumental role in growing the Gardens since the 1930s. Marketing and communications director Lauren Smith Hong highlights the women of Duke Gardens.

During my first visit to Duke Gardens, I walked into Kirby Horton Hall at the Doris Duke Center and was immediately drawn to the oil portraits of three women on the west wall. Something about the steely determination and strength in their gazes made a profound impression on me; without knowing exactly who they were, I instinctively knew that they had made a difference.

I soon learned that the three generations of women in the portraits—Sarah P. Duke, wife of Duke benefactor Benjamin Duke and the namesake of the Gardens; Mary Duke Biddle, Sarah’s daughter; and Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans, Mary Duke Biddle’s daughter—had been instrumental in shaping the Gardens. And they were not the only women who made Duke Gardens what it is today. Ellen Biddle Shipman, a forward-thinking landscape architect, provided the design for the Terrace Gardens in the 1930s. Linda Jewell, current professor and chair of landscape architecture at UC-Berkeley, guided the development of the Culberson Asiatic Arboretum in the 1980s. Edith Edelman designed the Perennial Allée in the 2000s.

I wanted to learn more about these amazing women and draw inspiration from their efforts as I embark upon my own professional journey here. I was fortunate enough to connect with Ann Stock, a longtime Gardens volunteer who has done extensive research on the history of Duke Gardens and has developed a tour about the women who shaped the Gardens.

The Duke Women

We started the tour in front of those legendary oil portraits of the Duke women.

Sarah Pearson Duke, renowned for her generosity as well as her gardening prowess, provided the initial funding to create a garden on Duke’s campus. She was no stranger to horticultural excellence. Four Acres, the Duke home in Durham, was said to be the best landscaped property in the area. Sarah was also instrumental in the landscape design of Duke’s campus, employing her considerable knowledge of species that thrived in Durham. In fact, Sarah’s daughter-in-law, Cordelia Drexel Biddle Duke, credited Sarah with enhancing the careers of the famed Olmsted brothers of New York through her contributions to the campus design. The areas she touched were among the most successful plantings on campus.

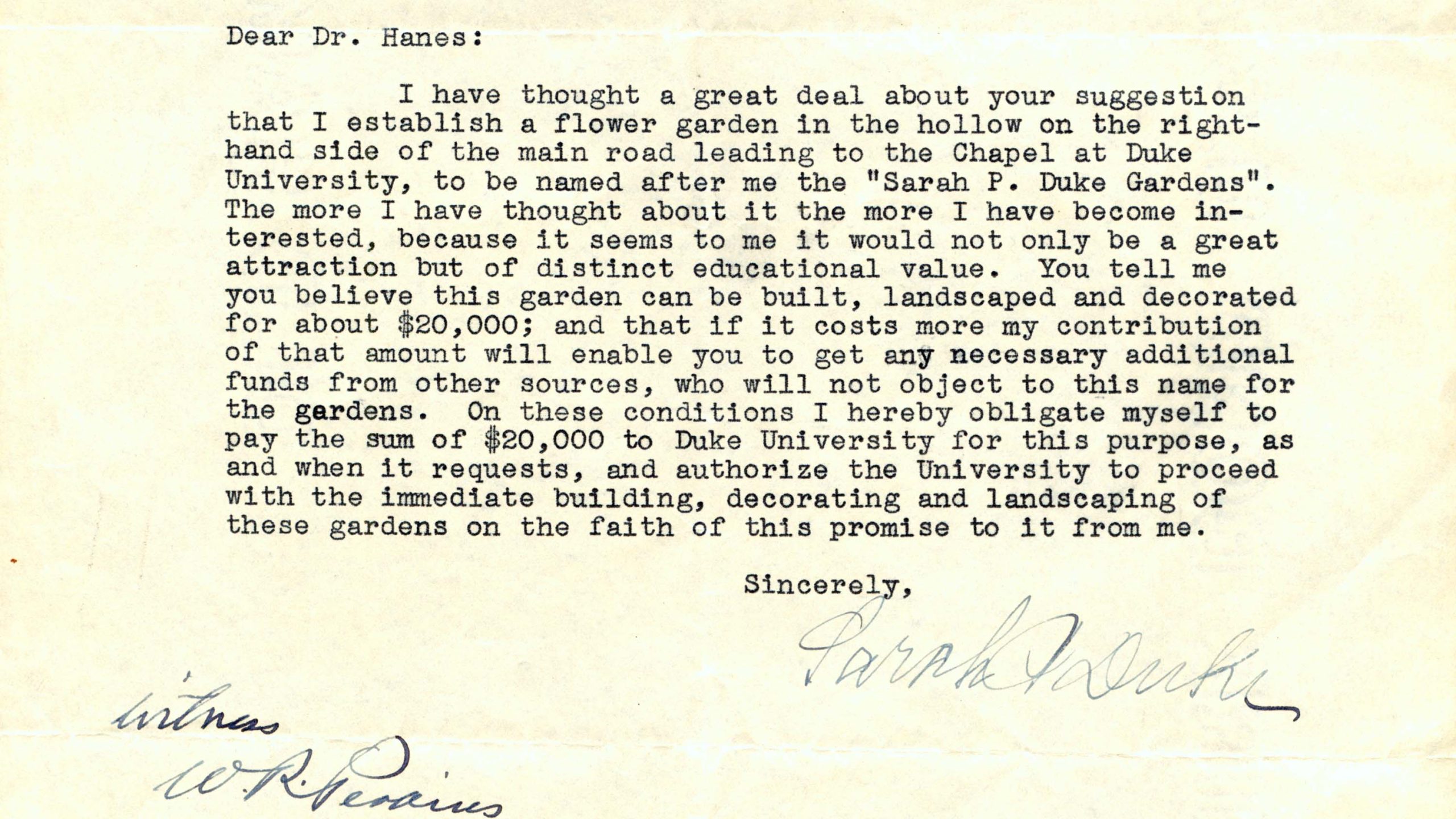

Dr. Frederic M. Hanes, one of the first faculty members of Duke’s Medical School, campaigned to convert the debris-filled ravine that he walked by daily into a garden of irises, his favorite flowers. He approached his friend Sarah for the lead gift. She agreed, and Sarah P. Duke Gardens was born. In a letter to Dr. Frederick Hanes from 1934, Sarah wrote:

“I have thought a great deal about your suggestion that I establish a flower garden in the hollow on the right-hand side of the main road leading to the Chapel at Duke University, to be named after me the “Sarah P. Duke Gardens.” The more I have thought about it the more I have become interested, because it seems to me it would not only be a great attraction but of distinct educational value.”

Sarah P. Duke in her garden in Durham, N.C.

Letter from Sarah P. Duke to Dr. Frederic Hanes, approving the creation of Sarah P. Duke Gardens

Sarah P. Duke Gardens in 1935

In 1935, more than 100 flower beds were in glorious bloom in the area that is now the South Lawn. They included 40,000 irises, 25,000 daffodils, 10,000 small bulbs, and assorted annuals. Alas, heavy summer rains caused washouts and disease, including iris rot. By the time Sarah P. Duke died in 1936, the original gardens were in decline.

Enter Mary Duke Biddle, Sarah’s daughter. A passionate philanthropist, Mary stepped into her mother’s shoes to revive Duke Gardens. Mary had forged a close connection to Dr. Hanes, who had helped her through a debilitating period of depression following her divorce from Anthony Drexel Biddle. In many ways, Mary felt indebted to Dr. Hanes for her life, and she was happy to provide funding to construct a new garden on higher ground as a fitting memorial to her mother. The Terrace Gardens as we know them today are the result of Mary’s generosity. She also funded the first greenhouses at Duke Gardens, with the stipulation that she would be able keep her own plants there in the winter.

Mary Duke Biddle

Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans in front of the Roney Fountain

Mary’s daughter, Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans, or “Little Mary,” continued the family’s support of the Gardens. She felt a great sense of responsibility to her family’s heritage and to caring for others, as well as a sense of obligation to the world at large. In fact, she served two terms on the Durham City Council. When she was first elected, one of the men on the council called Mary and another woman who had won a seat and asked them to resign immediately, citing the difficulty of talking business with women in the room. Mary just laughed and assumed her seat, knowing that her desire to help the community transcended farcical gender politics. In a way, this sense of duty marked her contributions to Duke Gardens as well; whenever she saw a need, no matter how unglamorous, she stepped up to help. In fact, her beloved second husband, Dr. James Semans, once remarked that the Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans Foundation preferred to fund “things that were neglected by other foundations.”

Duke Gardens held a special place in Little Mary’s heart, as she had adored her grandmother Sarah. In an interview with Charlie Rose, Mary recalled blissful summer days spent at Four Acres, where Sarah imbued every minute with a great sense of fun. She even made fried squirrel for her grandchildren! When Mary’s seven children decided to honor their parents’ 35th anniversary, they looked to the Gardens because of this special family connection. The sundial in the Butterfly Garden was dedicated to the Semanses, a fitting gift for a couple that was a ray of sunshine for so many.

Mary Semans also played a role in the redesign of the Mary Duke Biddle Rose Garden, which was named in her mother’s honor. The Roney Fountain, which was installed in the center of the Rose Garden in spring 2011, originally served as a focal point at the entrance to Trinity College (now Duke’s East Campus). Anne Roney, sister-in-law of Washington Duke, donated the fountain to Trinity College in Washington Duke’s honor in 1897. The fountain fell into disrepair over the decades and was overshadowed by massive magnolia trees. Duke Gardens, meanwhile, was seeking a fountain. An early master plan for the Rose Garden had called for one, but it had never been built. A bequest from the late Dr. J. Robert Teabeaut II (T’ 45, M.D. ’47) in honor of Mary Semans funded the fountain’s restoration, and Mary Semans’ desire to restore the Roney Fountain, which had been so important to her family’s heritage, was fulfilled. As Duke Gardens Executive Director William LeFevre noted at the Rose Garden dedication, “We at Duke Gardens are thrilled to be able to restore the Roney Fountain to a place of prominence on the Duke Campus and to honor the legacy of four generations of Duke women who helped make the campus what it is today.”

The Pioneering Architects & Designers

As Ann Stock and I ventured into the Gardens, I asked her what had inspired her research into the women of Duke Gardens. Ann chuckled and said, “I wanted to know how Mary Duke Biddle and Ellen Biddle Shipman were connected!” Ellen Biddle Shipman, the gifted landscape designer of the Historic Terrace Gardens, was indeed related to Mary Duke Biddle through marriage. Shipman was the daughter of Colonel James Biddle, a cousin of the Drexel Biddle family of Philadelphia. She spent her childhood on the western frontier until age 10, when she was sent to live with her grandparents in New Jersey. It was during this time that she developed a passion for cottage gardens filled with flowers, a love that she carried into her landscape designs as an adult.

Ellen Biddle Shipman became a landscape architect as the result of several fortuitous events. When she was housesitting for architect Charles Platt, she accidentally left behind some garden plans she had sketched, which caught Platt’s eye. At the time, he was designing estates around the country, and he encouraged her to pursue landscape design for private homes, going so far as to arrange for a designer in his firm to tutor Shipman in drafting.

By 1920, having secured a number of clients through her connections, Shipman opened her own landscape design firm in New York City. Not surprisingly, firms at the time did not hire women as designers. If she wanted to work professionally, she had to do so on her own. Shipman shunned convention – and moved the dial in the world of design – by only hiring women to work with her.

Most of Shipman’s designs were for private estate gardens, by some estimations more than 650 estates across the country. It was through her work with Ralph and Dewitt Hanes in Winston-Salem that she first met Dr. Frederic Hanes, Ralph’s brother. In the late 1930s, after the devastating floods at the original Sarah P. Duke Gardens, Hanes invited Shipman to visit the site and suggest a solution for the flooding problem.

Shipman developed a plan for a hillside terraced garden that was defined by strong axial lines, dovecotes and lush beds filled with roses and trees, reminiscent of English border gardens. Sensory elements abounded, such as flowing water features, classical statuary and secluded resting spots. Shipman employed Elizabeth Strang, one of her colleagues, to draft the plans for the garden, leaving Strang to design many of the non-floral features such as the Pergola.

Landscape architect Ellen Biddle Shipman

Blueprint of the pergola in the Terrace Gardens, drafted by Elizabeth Strang, who worked in Ellen Biddle Shipman’s firm.

Ellen Biddle Shipman’s plans for the Terrace Gardens

The Terrace Gardens under construction, 1938

The completed Terrace Gardens in 1939

The Terrace Gardens today

The result was the Terrace Gardens, much like they appear today. The garden was dedicated in 1939, and it quickly became a beloved gathering place for the Duke and Durham communities. In one of her garden notebooks, now housed in the Cornell University archives, Shipman wrote, “Gardening opens a wider door than any other of the arts – all… can walk through, rich or poor, high or low, talented or untalented. It has no distinctions, all are welcome.” She foresaw what would become the hallmark of Duke Gardens: a world-class botanic garden that is free and accessible to everyone.

“Gardening opens a wider door than any other of the arts – all mankind can walk through, rich or poor, high or low, talented and untalented. It has no distinctions, all are welcome.”

Ellen Biddle Shipman

The Legacy Continues

Ellen Biddle Shipman’s legacy continued through the work of renowned landscape architect Linda Jewell, now chair of landscape architecture and environmental planning at UC Berkeley. Jewell’s major contributions to Duke Gardens were the design of the large pond in the Culberson Asiatic Arboretum and the Blomquist Pavilion in the Blomquist Garden of Native Plants. As the early founders of Duke Gardens discovered in the 1930s, the geographic basin in which the Gardens is located is susceptible to flooding due to runoff from areas above the Gardens. Civil engineers in Duke’s School of Engineering had proposed a catchment basin capable of storing and slowly releasing up to 300,000 cubic feet of water. Practical? Yes. Aesthetically pleasing? Not so much.

William Culberson, director of Duke Gardens in the late 1970s and 1980s, turned to landscape architect Linda Jewell, partner at the firm Reynolds and Jewell in Raleigh (and designer of Cary’s Booth Amphitheatre, among other projects), for a better solution. She worked closely with engineers to design an attractive pond that would become the center of the Asiatic Arboretum and guide its overall development. Culberson credited Jewell for coming up with what he felt was the perfect solution. “The 1.5-acre pond is exceptionally beautiful, and the floods are a thing of the past,” he wrote in a letter of recommendation for Jewell in 1990. In 1981, Jewell won a special recognition award from the American Society of Landscape Architects for her work at Duke Gardens. But perhaps more important, her design has become a cherished landmark for visitors, not to mention a beloved home for ducks.

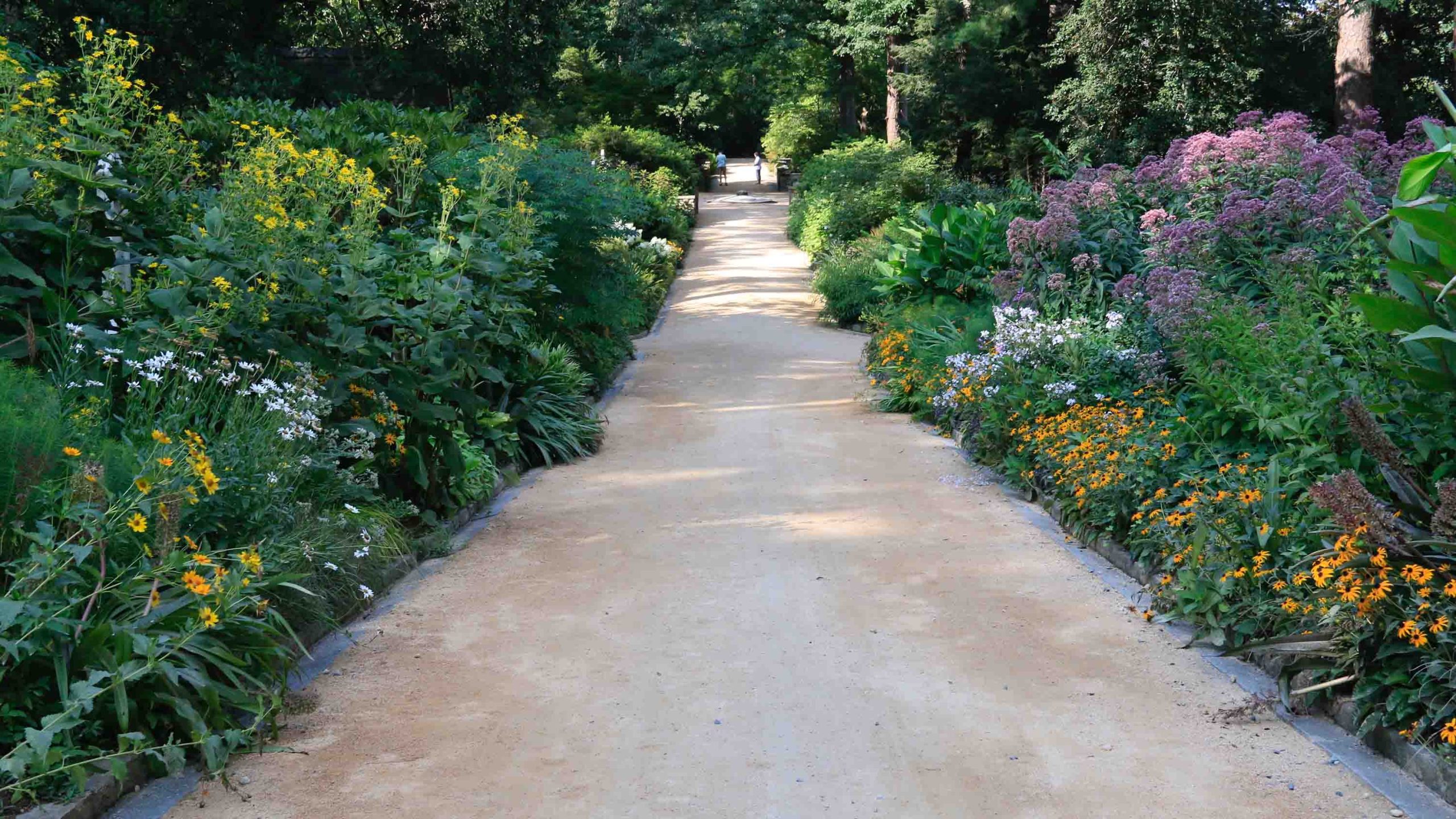

Edith Edelman carried Jewell’s torch along by contributing to the design of the Gardens through her work in the Walker Dillard Kirby Perennial Allée. The allée, which connects the Mary Duke Biddle Rose Garden to the Historic Terrace Gardens, was originally planted with annuals such as pansies, which posed a problem in the days when balls were allowed at Duke Gardens. As you can imagine, balls frequently landed in the beds, and resident flora were frequently trampled. Edelman, a Durham resident and perennial expert, along with her partner, Doug Ruhren, were brought in to transform the pathway borders with larger-scale perennials such as Spanish bayonette and other cacti, in part to deflect ball issues (both literally and figuratively!). Edelman is responsible for designing the beautiful trellises in the Perennial Allée, which are modelled after the gothic arches found across Duke’s campus.

Linda Jewell played an important role in designing the Culberson Asiatic Arboretum.

Edith Edelman’s influence is seen throughout the Walker Dillard Kirby Perennial Allée.

As Ann wrapped up the tour, an overwhelming sense of pride welled up inside me. How incredibly lucky I am to work at a place shaped by so many pioneering women. How lucky we all are to be able to experience their contributions firsthand with every visit to the Gardens. Sarah, the Marys, Ellen, Linda, Edith. And the list continues to grow as Duke Gardens grows as an institution. If the future is female, Duke Gardens is leading the way.

Questions about the history of Duke Gardens?

Please contact us at gardens@duke.edu.